By Elliot Crossan

Shellshock. That’s what much of the New Zealand left is feeling, having watched the Labour Party lose an unprecedented number of votes on 14 October. As the country waits to see whether National will need both ACT and NZ First to govern, the painful postmortem has begun. How could Labour fall from an historic 2020 landslide — its best result in 74 years — to losing nearly half of its vote in 2023?

The debate between the left and right of the Labour Party will take the same form it always has. The left will claim that the Sixth Labour Government was too cautious and too moderate; it failed to deliver major reforms such as a wealth tax; it failed to ‘transform’ Aotearoa as Jacinda Ardern promised in 2017; and thus it alienated its working class base. The centrists will argue that the Government went too far in pursuing change, failed to take “middle New Zealand” with it, and needed to slow down and take a more incrementalist approach.

The left’s argument needs to go beyond simply “Ardern and Hipkins did nothing for workers and workers abandoned them.” Valid as that is, there is a more nuanced truth here. The Labour Party did far too little to inspire the working class to turn out and vote for it, whilst also alienating the top 1%. Aotearoa’s richest turned decisively against the Government last term, and bankrolled National and ACT all the way to victory.

Labour’s campaign slogan was “In It For You.” To win again, MPs and party members need to ask themselves: who exactly are we in it for? A government cannot both win the support of the working class and appease the rich — it needs to pick one side or the other. The party leadership failed to pick either side, and crushing defeat was the price they inevitably had to pay.

A Doomed Campaign

The Labour right’s explanation for the party’s loss is not very compelling. The right of the party got the leader they wanted when Ardern stepped down in January. Chris Hipkins ditched the rhetoric of “transformation,” scrapping or watering down several key policies, and moving the party to the right. Even before Hipkins, Ardern’s administration was never a radical one — it tied itself to a rigid set of fiscal rules from day one, committing to maintain the status quo of small government and low public debt that has created such high levels of inequality. Neither Ardern nor Hipkins ever demonstrated the political will to tax the rich in order to redistribute money from the wealthy back to ordinary people.

The left can point to strong evidence that workers and progressive voters abandoned the party at the voting booths. Turnout was down by 3.8% from 2020, but this drop in turnout was not evenly distributed. As Henry Cooke showed on his Substack, in safe Labour seats such as Māngere and Manurewa — both working class electorates — turnout on the preliminary results was down by 12,572 votes and 10,453 votes respectively. In middle-class National strongholds such as Selwyn and Whangaparāoa, turnout was only down by 2,444 votes and 7,733 votes.

This election saw the biggest swing from National to Labour ever recorded. No doubt a large part of that was traditional middle-class National voters who voted for Labour during the Covid landslide returning home — but this meant that Labour would need to increase voter turnout to win. The party needed to bring in the communities most likely to vote Labour who so often do not vote — young people, low income people, Māori and Pasifika voters. The precise opposite happened, with working class turnout down.

Labour also lost votes to more progressive parties. The Green Party ran an unabashedly left-wing campaign, centred around the need to end poverty and act on climate change. Te Pāti Māori similarly campaigned on reducing inequality, continuing on the leftward trajectory it embarked upon last election, and ditching the neither-left-nor-right stance that saw the party booted out of Parliament in 2017, having propped up National for nine years.

Both parties campaigned on a “tax switch” — establishing a tax-free threshold and replacing the lost revenue with a wealth tax. The Greens wanted a $10K threshold; TPM wanted $30K.

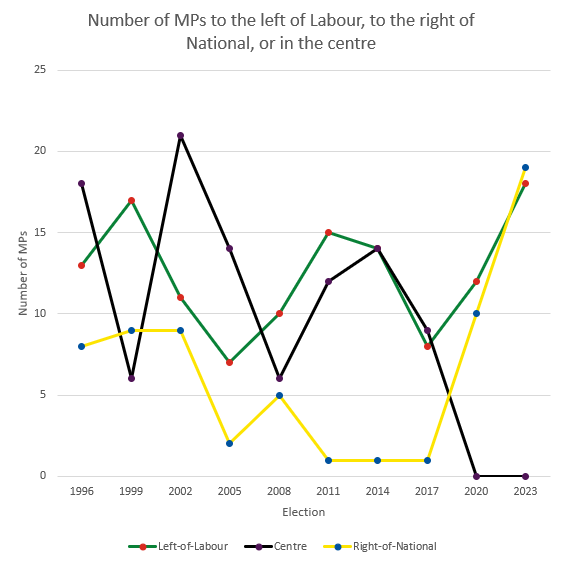

For both parties, this leftward shift paid off. The Greens matched their highest ever number of MPs and won multiple electorate seats for the first time, whilst TPM won four of the seven Māori electorates and their highest ever share of the party vote. There are now eighteen MPs to the left of Labour in the new Parliament — breaking a record set in the 1999 election, when the Alliance won ten seats and the Green won seven. Moving left is popular.

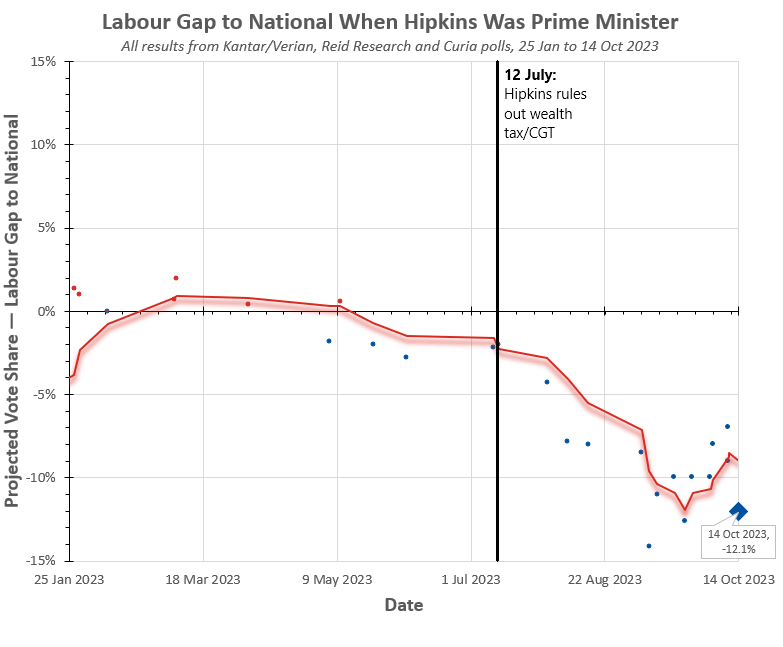

So exactly when did the wheels fall off Labour’s bid for a third term? Was it the 2023 Budget, which offered so little relief in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis? Was it the ministerial scandals that brought down Stuart Nash, Michael Wood and Kiri Allan? Or was it 12 July, the day Chris Hipkins ruled out implementing either a wealth tax or a capital gains tax? The latter date certainly coincides with Labour’s tight battle with National turning rapidly into a rout.

Support for taxing the rich was very strong. Three polls clearly revealed this — a Newshub-Reid Research poll in May showed majority support for a wealth tax; a 1 News-Verian poll in July revealed most people were in favour of a capital gains tax on rental properties; and most conclusively, a Guardian-Essential poll in September showed not only that 61% of Kiwis thought the wealthy should pay more tax, but that even half of National and ACT voters agreed.

Hipkins’ “captain’s call” on tax was a mistake for another critical reason: the country’s bleak economic outlook. For the next couple of years we can expect a global recession and little to no growth. Any new government spending will be limited. Labour needed to offer bold, popular policies to benefit ordinary Kiwis to make a third term worth voting for. To do so, it needed money. By ruling out significant changes to the tax system and sticking to tight fiscal rules, Hipkins ensured that Labour would have no ability to make major spending commitments.

Instead, huge electronic billboards across the country proudly proclaimed Labour’s ‘inspirational’ policies. GST OFF FRUIT AND VEG! Sigh. FREE DENTAL — and then in much smaller text — for under 30s. Then perhaps most pathetically of all: NO MORE $5 PRESCRIPTION FEES. Mr. Hipkins, if $5 a month was the best you had to offer, are you really surprised that you managed to lose 31 MPs?

The alternative was out there, and as the Greens and TPM showed, it was popular. Even within Hipkins’ own Cabinet, key figures were arguing for such a policy. Both Finance Minister Grant Robertson and Revenue Minister David Parker wanted a tax switch. Parker had already prepared the ground for this by commissioning a report from Inland Revenue which demonstrated comprehensively how broken Aotearoa’s tax system is. The findings showed that the wealthiest 311 Kiwi families pay less than half the average tax rate paid by ordinary households. Hipkins’ decision to rule out major tax changes was unilateral, and Robertson and Parker both confessed to being disappointed.

The time was right for a bold, unequivocal campaign. In campaigning for a tax switch, Labour would have been offering bigger tax cuts to the vast majority of Kiwis than National. We will never know how different the 2023 election result would have looked if Labour billboards had instead been emblazoned with: TAX CUTS FOR THE MANY, NOT THE FEW.

A No-Win Scenario

Why did Hipkins rule out taxing the wealthy? He claimed it was because it was “not the right time,” but amidst a cost-of-living crisis, never was the time more right to take the burden off workers and shift it to those who could afford to pay. It wasn’t to appease the mythical voters of “middle New Zealand” either, because as polling clearly established, the median voter supports taxing the rich.

The truth is that Hipkins was desperate to appease the only people who would lose out from taxing wealth — the super-rich. He was prepared to appease them even if it meant disappointing the majority of voters and hamstringing his policy platform.

It is therefore correct to argue that a large part of Labour’s defeat was caused by its campaign offering so little to workers. But that is not the only reason the Government fell. Labour may have compromised its platform significantly in an attempt to appease the rich. But it didn’t work. Hipkins ran directly into the trap that has ensnared so many Labour Prime Ministers before him. He watered down his offer to the working class in an attempt to win over business leaders and property owners who were already hell-bent on removing him from power.

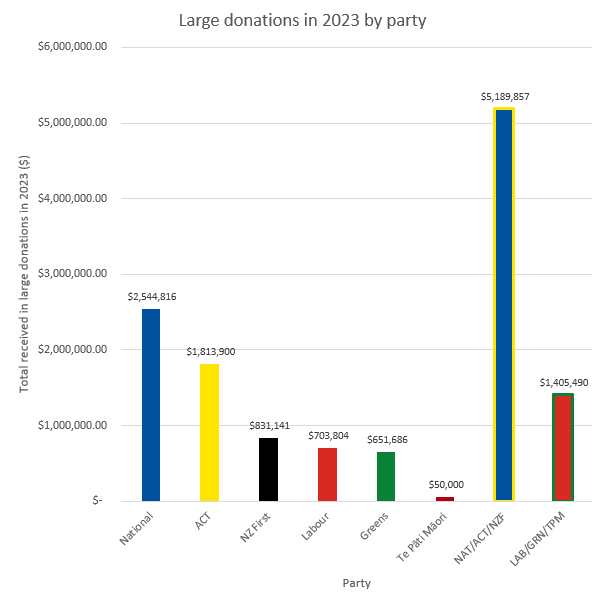

The question then arises: why were the rich so desperate to get rid of a Government that wasn’t even threatening to tax them? Why did the right-wing parties raise such staggering sums of money in 2022 — not even election year — that National received a record-breaking amount in donations? Why did National, ACT and NZ First receive nearly four times as much in large donations as Labour, the Greens and TPM — with Graeme Hart, the richest man in the country, splitting a $700,000 donation across the three right-wing parties, practically matching Labour’s total of $703,804? Why did ACT, a minor party, receive 2.6 times as much as the governing Labour Party?

The wealthy always prefer a National-led government. Right-wing parties govern in their interests, plain and simple. Even so, that doesn’t explain why during this election in particular campaign finance records were broken as capital poured in behind National, ACT, and NZ First. For all the justified condemnation of the Labour Party’s incrementalism and its failure to transform Aotearoa, the Government’s agenda — and one crucial policy in particular — did nevertheless represent a threat to the status quo.

The Flagship Policy That Never Was

With less than a year to go until the election, Labour quietly, almost apologetically, passed the biggest overhaul of workers’ rights Aotearoa has seen in decades. Fair Pay Agreements only played a small role in the election campaign, because Labour did a truly terrible job at promoting the very policy that should have been its flagship reform. It is the greatest tragedy of the Sixth Labour Government that FPAs, which would have been its lasting transformative legacy, will be repealed by National and ACT before their benefits have been felt and before most workers even know what they represent.

Fair Pay Agreements reintroduced sectoral bargaining, compelling businesses to gather around the table with unions to agree upon minimum pay and conditions across an entire sector. This would have meant significant gains for the likes of hospitality workers, security guards, cleaners and early childhood educators. It would also likely have produced the biggest increase in union membership in Aotearoa since the 1991 Employment Contracts Act broke the back of the 20th Century labour movement.

The fact that the Government passed the Fair Pay Agreements Act shows that the unions still wield enough power within the Labour Party to force even a moderate Labour Cabinet to implement real change in the interests of the working class.

No wonder the union movement mobilised in the final months of the election in an attempt to save the Government. It was no coincidence that the Council of Trade Unions made an uncharacteristically explicit intervention with an attack ad on the front page of the Herald and billboards across the country reading CHRISTOPHER LUXON: OUT OF TOUCH, TOO MUCH RISK. If a Labour-led coalition had won the 2023 election, there would have been enough time for multiple FPAs to come into effect, ensuring that the hundreds of thousands of workers impacted would have had a clear stake in defending their newly improved pay and conditions. It would have been so much more difficult for any future government to roll back these gains.

Why did Labour wait until the end of last year to implement this crucial reform? Was it because they hoped to string the unions along into campaigning for a third term? Whatever the case, it was a catastrophic decision not to rush FPAs through with as much urgency as possible. Once workers felt the benefits, this policy — even more so than the abandoned tax switch — could have been an easy election-winner for Labour.

Now it is too late. Scrapping FPAs is one of the top items on National’s agenda for its first 100 days. Bosses across Aotearoa were determined not to grant higher wages, overtime pay, weekend and night rates, more sick days, more holidays, and everything else the unions could have negotiated. Perhaps then, instead of being the transformational legacy of the Sixth Labour Government, this policy was the defining reason why the rich mobilised to ensure a National victory.

There were plenty of other progressive reforms the rich sought to undo. Labour’s ban on no-cause evictions and 90-day trials are set to be abolished by National, whilst ACT wants to take away five sick days for workers and reduce the number of public holidays. But FPAs would have empowered the labour movement more than any other reform, and that in particular is unconscionable to the wealthy.

The Sixth Labour Government tried to triangulate between the interests of bosses and workers; between the rich and the poor. It ended up alienating both.

Which Side Are You On?

In all their debriefs and postmortems, Labour MPs need to stop fixating upon this or that superficial ministerial cock-up and resist the temptation to blame it all on their leader’s personal brand. Instead they’d do well to ask themselves just one question, the title of a famous union song: Which Side Are You On? The answer should be blindingly obvious to the Labour Party. It’s in the name. Labour. Labour needs to champion the working class it was founded to represent. It needs to clearly, unambiguously campaign in the interests of the many, not the few. Because if it doesn’t, the party will continue to alienate its own supporters, and will never make truly transformational change.

There is, of course, a false lesson from this argument that the centrists can take and run with: we were right! We did change too much, too quickly. We shouldn’t have raised benefits more than any other government in the last few decades. Fair Pay Agreements were too far — we need to reduce the power of the unions within the Labour Party once and for all. To govern, we need to appease the rich at all times, and to do so, we must drive the left out of politics and forget about the working class.

Using this strategy, they may indeed win over some wealthy donors. But it would at best be short-term gain for long-term pain. Abandoning the working class means that turnout will fall further, and left-wing voters will get more and more alienated by the Labour Party. Big business will always prefer a National Government anyway, because National is their party.

In the last decade, social democratic parties across Europe have felt the devastating impacts of abandoning the working class. The collapse of the Greek centre-left party PASOK after it betrayed workers and implemented severe austerity in the early 2010s led to the term “Pasokification” being coined.

Many centre-left parties across the continent suffered this fate and were outflanked by parties championing more radical policies. For example, the once-mighty French Parti Socialiste finished tenth in the 2022 presidential election, whilst the more radical La France Insoumise nearly made it to the second round run-off. If Labour chooses to abandon workers and move even further to the right in the wake of its devastating defeat, Pasokification is its inevitable fate.

Those who fear backlash from the wealthy must remember that the wealthy will always oppose any reform that goes against their interests, no matter how mild. So fight back. Win over the support of the workers by inspiring them to vote for change. After all, the offer of transformational change is what got Jacinda Ardern elected in the first place.

The next Labour leader must campaign to tax the rich. That is beyond doubt. In doing so, they will be able to advocate for a series of reforms that will be wildly popular and urgently necessary for the working class. They could start by supporting the Greens’ call for free dental care and TPM’s call for a $30K tax-free threshold.

But even more crucially, Labour needs to return to its roots and put workers’ rights at the centre of its agenda for the future of Aotearoa. What if in 2026, workers are given the option of voting for a Labour Party that is promising a living wage for all; further increases to mandatory paid sick leave, parental leave and holidays; penal rates for overtime, weekend and night shifts? The prospect of an economy that is liveable for workers, where young people can build a stable life instead of fleeing to Australia?

It won’t be easy. The rich will pour unprecedented money and resources into stopping Labour at all costs; and the corporate-owned media will demonise any leader who dares to fight for such a programme. But it will tap into the only resource Labour can truly rely on if it wants to both win elections and make meaningful, lasting change: the power of the people.

Only a mass movement of workers can defeat the wealth and power of the super-rich. There are no short-cuts to change, and there is no perfect triangulation between the interests of bosses and workers that will ever be acceptable to both. So take a side.

If Labour does not take the side of the working class, and does not offer a truly transformational vision for the future of Aotearoa, then it will slide into irrelevance. The party needs either to change now, or make way for those who are prepared to meet the challenges of our time.

The Struggle Ahead

The centre is collapsing in Aotearoa. There are more MPs to the left of Labour than ever before — 14 from the Greens and 4 from Te Pāti Māori — and more MPs to the right of National than ever before — 11 from ACT alone is a record, let alone the 8 from the rightward shifting NZ First. Gone is the era when bland managerialism, as offered by Chris Hipkins, was the way to win elections.

This new right-wing government is planning to implement austerity on a level most young Kiwis have never experienced before. Luxon and his team are planning to attack workers’ rights, and the ACT Party will do everything in their power to make those attacks as brutal as they possibly can. It is not going to be pretty.

But this will be a weak, divided government. Luxon is an uncharismatic leader, with nothing remotely approaching the popularity of John Key — and the National Party actually received a lower vote share than it did in any of the five elections between 2005 and 2017, despite losing two of the aforementioned elections.

National will almost certainly need to work with both ACT and NZ First after the special votes. Both parties hate each other — ACT is a hardline neoliberal party that is occasionally mildly socially progressive, whilst NZ First is a nationalist party that is opposed to some neoliberal policies. Peters has literally tweeted threats of physical violence to Seymour in the past!

This coalition of chaos will be much easier to fight than the Key Government; and there is always hope when ordinary people fight back. Across Europe in the 2010s, anti-austerity movements not only produced resistance to unpopular attacks on the welfare state, but they also created a new form of left-wing politics which said no to the stale centrism of the 90s and 00s, and instead advocated genuine, radical change. It is likely that such movements will emerge here when the new government pursues its own austerity agenda in order to fund tax cuts for its wealthy donors.

When that time comes, it will be too late to start choosing sides. That is why the question must be posed to the Labour Party now. Stop trying to triangulate between the interests of bosses and workers, and ask: which side are you on?

Elliot Crossan is a socialist writer and activist from Auckland.